Tempered Pride

- Karen Derrick-Davis

- Nov 10, 2025

- 4 min read

As I research my ancestors, I feel pride and admiration for their sense of adventure, fortitude and entrepreneurial spirit. The common theme of the stories of my “first arrivers” is “immigration by choice” – for one reason or another, they chose to move to North America. Some were escaping oppression—economic and/or religious (sometimes so intertwined, it is hard to separate them). Others who already had resources, seemed motivated primarily by the opportunities to increase their wealth and prosperity in the “New World.”

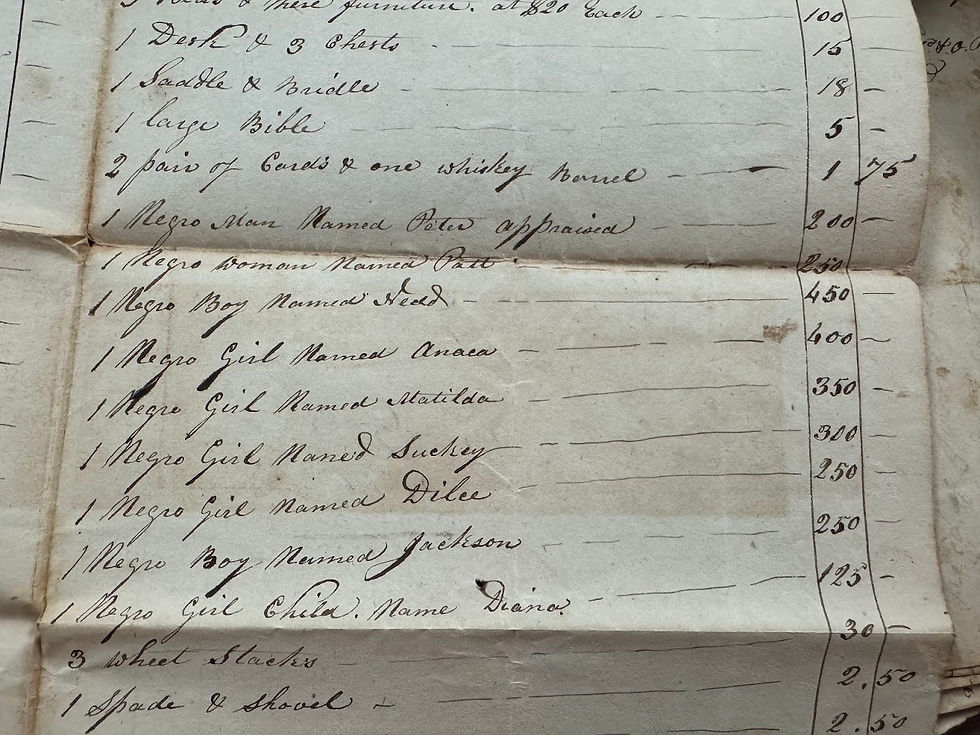

Most of these first arrivers immigrated between the 1630’s and the late 1700’s -- when the economy of Colonial America depended on chattel slavery. I have found wills, property inventories, tax records and censuses that document the numerous enslavers in my ancestral family and the even more numerous people enslaved by them. The discovery was not unexpected, but shocking, nonetheless.

To say the least, any pride I feel for my ancestors is tempered by the fact they were enslavers. Even when a morsel of compassion is found in a record, such as Samuel John Greer directing in his will that enslaved couple Peter and Pat “not be sold or bartered away but to treat them in a human like manner their labour to be as equal between them.” I cannot help but roll my eyes and scoff. The fact remains: he enslaved other human beings – he controlled the fate of the lives of Peter and Pat and others, as well as the lives of all their descendants, fully, completely.

Sometimes people today, say, “Well, that was a different time. We shouldn’t judge others through today’s lens.” Not buying it. My ancestors came from Europe and chose to settle in areas where slavery was practiced. They willingly joined that economy. They even fought and risked their lives in the Civil War to maintain the livelihood that depended on enslaving others. They increased their wealth and prospered on the backs of others. They bought and sold people. Period.

I do not believe all my enslaver ancestors were evil and vicious people, but I do wonder, “What amount of mental gymnastics and rationalizing were necessary for kind, compassionate people to enslave others?” The same man who instructed Peter and Pat to be treated in a “human like manner” appeared to have split up other families and sell off single children with no remorse or reservations. He was only the first of four generations of enslavers of the Greer family in Kentucky – only one line of the multi-generational enslavers in my family. I have found no evidence that anyone in my family freed any enslaved person before they were forced to do so.

In some old family papers, I found several chapters of an unfinished historical fiction written by my great-grandmother, Lillian Greer Bedichek. The story tells of her grandmother’s migration from her childhood home – a plantation in Alabama – to a new home, a plantation in Louisiana, with her new husband, John Bachman Greer (Samuel's great-grandson). In the piece, she presents a picture of reciprocal endearment between enslavers and enslaved. The enslaved are called “servants” and the relationship is portrayed as one of mutual caring – with no mention of the chattel slavery inherent in the relationship. Throughout her lifetime, Lillian was a progressive woman, fighting for the oppressed and advocating for progressive issues in her lifetime – how could she write about slavery in her own family with such a “Gone with the Wind” feel? It baffles me.

I cannot change history. I CAN, however, report it faithfully to highlight my family’s place and in it. I will not sugarcoat or excuse ancestral bad behavior. History is full of exploitation, however, it is harder to stomach it when it is so directly connected to me. What I am learning is that this history of slavery in this country is not so distant and, in fact, feels more and more like yesterday.

******

Eliminating history that makes us feel bad is not only wrong, but incredibly dangerous. The only way forward is by owning and acknowledging these truths. We cannot learn from mistakes if mistakes are erased – like from our national museums and school history books. It should make us feel bad!

I do not profess to know the Bible well, but I do believe this verse: “whoever conceals his sins will not prosper, but he who confesses and renounces them will find mercy.” (Proverbs 28:13) The interpretations of this passage stress the importance of public confession – that the weight of holding on to the sins is more damaging than confessing them. As a country, we will continue to pay for the sin of slavery, Jim Crow, and the racism that persists in our country until we completely own it (without any caveats) and publicly confess and admit that the work of repair is not finished.

It is hard to believe that Grandma would write about slavery in her family as mutually endearing.

Good piece.